The following story was originally published in the “Perspective on the Past†column of Snohomish County Senior Services newspaper, Senior Focus, the April-May 2011 edition.

Photos Leave a Lasting Impression of Life

By Louise Lindgren

c. 2011 All Rights Reserved

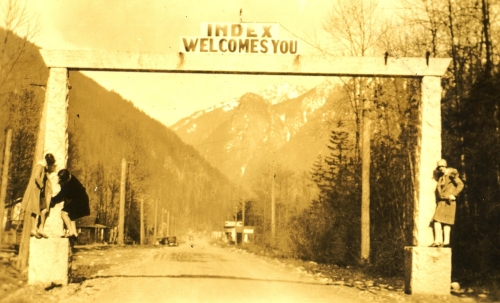

The small photo in an old black album riveted my attention. Yes, there were the two granite columns and the wooden cross piece, letting people know they were welcome in the town of Index. All was just as I had drawn it on a small scrap of paper under the direction of longtime Index resident Wes Smith, back in 1982. It was a rough pencil sketch from my imagination and his memory, for no such welcoming portal had been seen on the old road entering town since the 1920s.

Index Welcomes You

Until that remarkable album find in 2009 no one in our historical society had seen any image showing the long-ago abandoned main entry to the town. Wes had nothing, except in his memory, and there was no such photo to be found in the hundreds taken here by Lee Pickett, a commercial photographer whose collection was given to the University of Washington by his widow, Dorothy. She corroborated Wes’ memory on that day back in 1982 when I inexpertly drew that likeness. I had been looking for an original image ever since.

There are two remnants of the portal left. One pillar, quarried from the granite that dominates cliffs behind the town, sits on its matching block near the corner of 6th and Avenue A. With its attached bronze plaque, the monument serves as a memorial to Index pioneer William Ulrich. One block, pillar missing, sits on its original site. Until the photo surfaced, few townspeople knew an entry portal existed when Avenue A was the main road into town.

The road entered at that western point having wound its way tortuously up through many turns – one evocatively named “The Devil’s Elbow†— from Gold Bar, over a long ridge that is now primarily state park land. Now named the Reiter Road, in the 1920s it was the state’s first official scenic highway, the “Cascade Highway,†which crossed Stevens Pass. It was fitting for the town to have a monumental structure to welcome all those cross-state travelers and fitting that three young ladies would choose to pose on those stones as they took a break after a grueling drive on that unpaved road.

Sometimes the most important pieces of information — images, drawings, documents, memorabilia and artifacts — come to a museum from far away, totally unexpected and long removed from the time they were first connected with the story of a community. These are the happy surprises – few and far between. When we began collecting the history of the town of Index in an organized way in 1982, already much had been lost.

People moved away in the 1930s, taking their family albums with them. Early Index residents died, having passed those albums, in many cases, to children who were born elsewhere, having no story connections to most of the images. Often scrapbooks were cut apart, with only recognizable people pictures saved – the rest discarded as trash because it was thought that no one would care.

That might have happened to this rare image of the town’s entry as well, had it not been for the foresight, responsibility, and caring of Ruby Egbert’s friend, Bob Morse. He inherited her memorabilia and could have taken a shortcut to its disposal by ignoring the fact that her album had images of Index, where she lived for a short time. The photo I had been hoping would appear for over 25 years could have been tossed.

After all, the primary story about Ruby was not the fact that she was a young person in Index, but that she earned fame as the woman who donated money to buy and preserve 75 acres with 6,000 feet of shoreline which became the Ruby E. Egbert Natural Area of Bottle Beach State Park at Grays Harbor. After leaving Index, she had a career as a librarian with the Washington State Library in Olympia and was a dedicated bird watcher and world traveler. Although she did not live long enough to see that area’s dedication ceremony in July 2009, The Olympian newspaper praised her efforts as a benefactor to her beloved birding territory by the seashore.

When the writer decided to open the article about the dedication of that natural area with the sentence, “All of us leave an impression on this planet,†the intention was to honor Egbert for her great environmental gift. No one recognized at that time that her legacy would live on in the small town of Index, as the person who saved the photo and placed it in an album which would eventually make its way “back home†to the place where she lived and cavorted with her friends for a while by the entry to town.

How many more albums are out there, sitting in dusty corners of antique shops, or worse, moldering away under piles of garbage at a county dump? How many shoeboxes and scrapbooks hold pictures that could answer the questions of those who seek their community’s history? We historians honor not only those who took the time to make the images and save them for “someday,†but those, like Bob Morse, who recognize the importance of adding to the community memory by saving and sharing those open windows to the past.

Perhaps you have created such collections, or inherited them from relatives.  Suggestion: if your children show no interest right now, bet that they may in the future. Often people become interested in their own family history too late, in their forties or older, when they finally find the time. Often that’s too late – the photos have been discarded, or the family member who could add information to the image has passed on.

Go ahead, make copies of those pictures, adding words that will tell the story. Have faith that the time spent is worth it, and give photos and information not only to relatives, but to any historical groups that are appropriate. If you find an album in a second hand store and recognize the area where the photos were taken, you might find a grateful museum director who, as I, had been looking for just that information. In this seemingly small way, you too will have added to the impression you can’t help but leave on this planet.